Human Orbital Spaceflights

![]()

International Flight No. 68Soyuz 33SaturnUSSR |

|

|

|

||

![]()

Launch, orbit and landing data

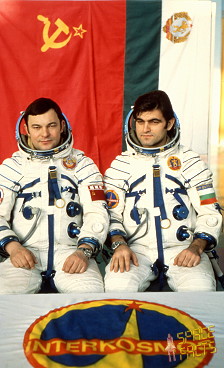

walkout photo |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||

Crew

| No. | Surname | Given names | Position | Flight No. | Duration | Orbits | |

| 1 | Rukavishnikov | Nikolai Nikolayevich | Commander | 3 | 1d 23h 01m 06s | 31 | |

| 2 | Ivanov | Georgi | Research Cosmonaut | 1 | 1d 23h 01m 06s | 31 |

Crew seating arrangement

|

|

|

||||||||||||

Backup Crew

|

|

|||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

Hardware

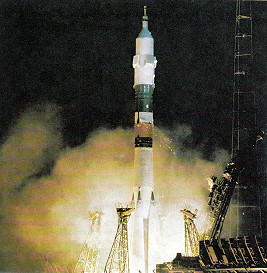

| Launch vehicle: | Soyuz-U (No. Zh15000-182) |

| Spacecraft: | Soyuz 33 (7K-T No. 49) |

Flight

|

Launch from the Baikonur Cosmodrome and

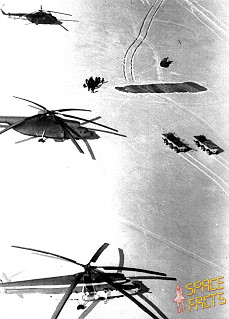

landing 316 km southeast of Dzheskasgan. Soyuz 33 carried the fourth Intercosmos mission (with Georgi Ivanov, the first cosmonaut from Bulgaria). At 9 km distance from the station, the Igla automatic docking system was activated. But, as the craft approached to 1,000 meters, the engine failed and automatically shut down after three seconds of a planned six-second burn. Nikolai Rukavishnikov had to hold the instrument panel as the craft shook so violently. After consulting with ground control, the docking system was activated again, but the engine shut down again, and Valeri Ryumin, observing from the station, reported an abnormal lateral glow from behind the Soyuz during the burn. Mission control accordingly aborted the mission and told the crew to prepare to return to earth. It was the first in-orbit failure of the Soyuz propulsion system. The failure was determined to be a malfunction of the main engine. A pressure sensor in the combustion chamber was shutting down the engine when it seemed normal combustion pressure was not being reached. This shut-down mechanism was designed to prevent propellants from being pumped into a damaged engine thus risking damage and/or an explosion. It was only in 1983 that the Soviets revealed how serious the situation was. The craft had a back-up engine but it was feared that it may have been damaged by the main engine, potentially leaving the crew stranded with five days of supplies while it would take ten days for the orbit to decay. One option to return the crew if the backup engine was inoperable would have been to use attitude control thrusters to slow the Soyuz below orbit velocity. But there may have not been enough propellant to do this, and the landing point would have been unpredictable if it worked. Another option was to move the station to the Soyuz. The station could have been moved to within 1,000 m of the craft, at which point Soyuz 33 could be docked using its thrusters. But the two crafts were drifting apart at 28 meters per second, and time was needed to calculate the maneuvers. In any event, four crew on the station with one malfunctioning Soyuz and a second Soyuz (the station crew's Soyuz 32, already docked at Salyut 6) with a now-questionable engine (it had the same type as Soyuz 33) was not considered the best option. The Soyuz spacecraft is composed of three elements attached end-to-end - the Orbital Module, the Descent Module and the Instrumentation/Propulsion Module. The crew occupied the central element, the Descent Module. The other two modules are jettisoned prior to re-entry. They burn up in the atmosphere, so only the Descent Module returned to Earth. Having shed two-thirds of its mass, the Soyuz reached Entry Interface - a point 400,000 feet (121.9 kilometers) above the Earth, where friction due to the thickening atmosphere began to heat its outer surfaces. With only 23 minutes left before it lands on the grassy plains of central Asia, attention in the module turned to slowing its rate of descent. Eight minutes later, the spacecraft was streaking through the sky at a rate of 755 feet (230 meters) per second. Before it touched down, its speed slowed to only 5 feet (1.5 meter) per second, and it lands at an even lower speed than that. Several onboard features ensure that the vehicle and crew land safely and in relative comfort. Four parachutes, deployed 15 minutes before landing, dramatically slowed the vehicle's rate of descent. Two pilot parachutes were the first to be released, and a drogue chute attached to the second one followed immediately after. The drogue, measuring 24 square meters (258 square feet) in area, slowed the rate of descent from 755 feet (230 meters) per second to 262 feet (80 meters) per second. The main parachute was the last to emerge. It is the largest chute, with a surface area of 10,764 square feet (1,000 square meters). Its harnesses shifted the vehicle's attitude to a 30-degree angle relative to the ground, dissipating heat, and then shifted it again to a straight vertical descent prior to landing. The main chute slowed the Soyuz to a descent rate of only 24 feet (7.3 meters) per second, which is still too fast for a comfortable landing. One second before touchdown, two sets of three small engines on the bottom of the vehicle fired, slowing the vehicle to soften the landing. The main option was to fire the back-up engine, but this option was not guaranteed to work, even if the engine fired. The nominal burn time was 188 seconds, and as long as the burn lasted more than 90 seconds, the crew could manually restart the engine to compensate. But this would mean an inaccurate landing. If, however, the burn was less than 90 seconds, the crew could be stranded in orbit. A burn longer than 188 seconds could result in too-high loads on the crew during re-entry. In the end, the backup engine did fire, though for 213 seconds, 25 seconds too long, resulting in an unusually steep trajectory and loads of 10 g's to be endured by the crew. Nikolai Rukavishnikov and Georgi Ivanov were safely recovered. It was the second ballistic entry reported by the Soviets, Soyuz 1 being the first. Others noted that Soyuz 18A was a ballistic reentry, and Soyuz 24 reportedly also was one. An investigation lasted a month and found that the part that failed had been tested 8,000 times previously without failing, and the Soyuz engine had fired some 2,000 times since 1967, also without a single failure. But the engine was modified for the next flight. |

Photos

|

|

|

|

|

Credit: GTCT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| © |  |

Last update on March 28, 2025.  |

|